📝 Biased Estimation: Ridge Regression

In this set of notes, we will give a brief introduction to ridge regression. We will continue to use the equal-education-opportunity.csv data provided from Chatterjee & Hadi (2012) to evaluate the availability of equal educational opportunity in public education. The goal of the regression analysis is to examine whether the level of school facilities was an important predictor of student achievement after accounting for the variation in faculty credentials and peer influence.

A script file for the analyses in these notes is also available:

# Load libraries

library(broom)

library(MASS)

library(tidyverse)

# Read in data

eeo = read_csv("~/Documents/github/epsy-8264/data/equal-education-opportunity.csv")

head(eeo)Biased Estimation

The Gauss-Markov Theorem posits many attractive features of the OLS regression model. Two of these properties are that the OLS estimators will be unbiased and that the sampling variances of the coefficients are as small as possible1. In our example, the fitted model using faculty credentials, peer influence, and school facilities to predict variation in achievement showed strong evidence of collinearity; which makes the SEs super large even if they are the minimum of all possible linear, unbiased estimates.

One method of dealing with collinearity is to use a biased estimation method. These methods forfeit unbiasedness to decrease the size of the sampling variances; it is bias–variance tradeoff. The goal with these methods is to trade a small amount of bias in the estimate for a large reduction in the sampling variances for the coefficients.

The bias–variance tradeoff is a commonplace, especially in prediction models. You can explore it in more detail at http://scott.fortmann-roe.com/docs/BiasVariance.html.

Ridge Regression

To date, the most commonly used biased estimation method in the social sciences is ridge regression. Instead of finding the coefficients that minimize the sum of squared errors, ridge regression finds the coefficients that minimize a penalized sum of squares, namely:

\[ \mathrm{SSE}_{\mathrm{Penalized}} = \sum_{i=1}^n \bigg(y_i - \hat y_i\bigg)^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^p \beta_j^2 \]

where, \(\lambda\geq0\) is a scalar value, \(\beta_j\) is the jth regression coefficient, and \(y_i\) and \(\hat{y}_i\) are the observed and model fitted values, respectively. One way to think about this formula is:

\[ \mathrm{SSE}_{\mathrm{Penalized}} = \mathrm{SSE} + \mathrm{Penalty} \]

Minimizing over this penalized sum of squared error has the effect of “shrinking” the mean square error and coefficient estimates toward zero. As such, ridge regression is part of a larger class of methods known as shrinkage methods.

The \(\lambda\) value in the penalty term controls the amount of shrinkage. When \(\lambda = 0\), the entire penalty term is 0, and the penalized sums of squared error reduces to the non-penalized sum of squared errors:

\[ \mathrm{SSE}_{\mathrm{Penalized}} = \mathrm{SSE} \]

Minimizing this will, of course, produce the OLS estimates. The bigger \(\lambda\) is, the more the model’s residual variance estimate and coefficients shrink toward zero. At the extreme end, \(\lambda = \infty\) will shrink every coefficient to zero.

Matrix Formulation of Ridge Regression

Recall that the OLS estimates are given by:

\[ \mathbf{b} = (\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{y} \]

Under collinearity, the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) matrix is ill-conditioned. (A matrix is said to be ill-conditioned if it has a high condition number, meaning that small changes in the data impact the regression results. This ill-conditioning results in inaccuracy when we compute the inverse of the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) matrix, which translates into bad estimates of the coefficients and standard errors.

To see this, consider our EEO example data. We first standardize the variables (so we can omit the ones column in the design matrix) using the scale() function. Note that the output of the scale() function is a matrix. Then, we will select the predictors using indexing and compute the condition number for the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) matrix.

# Standardize all variables in the eeo data frame

z_eeo = eeo %>%

scale()

# Create and view the design matrix

X = z_eeo[ , c("faculty", "peer", "school")]

head(X) faculty peer school

[1,] 0.5158617 -0.01213684 0.1310782

[2,] 0.6871673 0.46812962 0.4901170

[3,] -0.8084583 -0.71996624 -0.7994390

[4,] -1.2024935 -1.36577136 -1.0479983

[5,] 0.1150408 -0.25030749 0.1078451

[6,] 0.1413252 0.08793894 0.2356566# Get eigenvalues

eig_val = eigen(t(X) %*% X)$values

# Compute condition number

sqrt(max(eig_val) / min(eig_val))[1] 19.25836We can inflate the diagonal elements of \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) to better condition the matrix. This, hopefully, leads to more stability in the inverse matrix and produces better (albeit biased) coefficient estimates. To do this, we can add some constant amount (\(\lambda\)) to each of the diagonal elements of \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\), prior to finding the inverse. This can be expressed as:

\[ \widetilde{\mathbf{b}} = (\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X} + \lambda \mathbf{I})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{Y} \]

where the tilde over b indicates that the coefficients are biased. To see how increasing the diagonal values leads to better conditioning, we will add some value (here \(\lambda=10\), but it could be any value between 0 and positive infinity) to each diagonal element of the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) matrix in our example.

Technically this equation is for standardized variables; it assumes that there is no ones column in the X matrix. This is because we only want to add the \(\lambda\) value to the parts of the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) matrix associated with the predictors.

# Add 50 to each of the diagonal elements of X^T(X)

inflated = t(X) %*% X + 10*diag(3)

# Get eigenvalues

eig_val_inflated = eigen(inflated)$values

# Compute condition number

sqrt(max(eig_val_inflated) / min(eig_val_inflated))[1] 4.500699The condition number has decreased from 19.26 (problematic collinearity) to 4.5 (non-collinear). Adding 10 to each diagonal element of the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}\) matrix resulted in a better conditioned matrix!

Ridge Regression in Practice: An Example

Let’s fit a ridge regression model to our EEO data. For now, we will choose the value for \(\lambda\). Let’s use \(\lambda=0.1\). It is recommended that you always standardize all variables prior to fitting a ridge regression because large coefficients will impact the penalty in the SSE more than small coefficients. Here we will again use the design matrix based on the standardized predictors we created earlier, and also the vector of y, also based on standardized values. Here we use the diagonal inflation value of \(\lambda=0.1\), just to illustrate the concept of ridge regression:

# Create y vector

y = z_eeo[ , "achievement"]

# Compute and view lambda(I)

lambda_I = 0.1 * diag(3)

lambda_I [,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 0.1 0.0 0.0

[2,] 0.0 0.1 0.0

[3,] 0.0 0.0 0.1# Compute ridge regression coefficients

b = solve(t(X) %*% X + lambda_I) %*% t(X) %*% y

b [,1]

faculty 0.4347370

peer 0.8552354

school -0.8491600The fitted ridge regression model using \(\lambda=0.1\) is:

\[ \hat{\mathrm{Achievement}}^{\star}_i = 0.435(\mathrm{Faculty}^{\star}_i) + 0.855(\mathrm{Peer}^{\star}_i) - 0.849(\mathrm{School}^{\star}_i) \]

where the star-superscript denotes a standardized (z-scored) variable.

Using an Built-In R Function

We can also use the lm.ridge() function from the {MASS} package to fit a ridge regression. This function uses a formula based on variables from a data frame in the same fashion as the lm() function. It also takes the argument lambda= which specifies the values of \(\lambda\) to use in the penalty term. Because the data= argument has to be a data frame (or tibble), we convert the standardized data (which is a matrix) to a data frame using the data.frame() function.

# Create data frame for use in lm.ridge()

z_data = z_eeo %>%

data.frame()

# Fit ridge regression (lambda = 0.1)

ridge_1 = lm.ridge(achievement ~ -1 + faculty + peer + school, data = z_data, lambda = 0.1)

# View coefficients

tidy(ridge_1)Comparison to the OLS Coefficients

How do these biased coefficients from the ridge regression compare to the unbiased coefficients from the OLS estimation? Below, we fit a standardized OLS model to the data, and compare the coefficients to those from the ridge regression with \(\lambda=0.1\).

# Fit standardized OLS model

lm.1 = lm(achievement ~ faculty + peer + school - 1, data = z_data)

# Obtain coefficients

coef(lm.1) faculty peer school

0.5248647 0.9449056 -1.0272986 Comparing these coefficients from the different models:

| Predictor | λ=0 | λ=0.1 |

|---|---|---|

| Faculty | 0.525 | 0.436 |

| Peer | 0.945 | 0.856 |

| School | -1.027 | -0.851 |

Based on this comparison, the ridge regression has “shrunk” the estimate of each coefficient toward zero. Remember, the larger the value of \(\lambda\), the more the coefficient estimates will shrink toward 0. The table below shows the coefficient estimates for four different values of \(\lambda\).

| Predictor | λ=0 | λ=0.1 | λ=1 | λ=10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty | 0.525 | 0.436 | 0.180 | 0.114 |

| Peer | 0.945 | 0.856 | 0.537 | 0.227 |

| School | -1.027 | -0.851 | -0.283 | 0.073 |

| Condition Number | 370.884 | 313.908 | 132.125 | 20.256 |

Examining these results we see that increasing the penalty (i.e., higher \(\lambda\) values) better conditions the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I}\) matrix, but a higher penalty also shrinks the estimates toward zero more (increased bias). This implies that we want a \(\lambda\) that is large enough so that it conditions the \(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I}\) matrix, but not too large because we want to introduce the least amount of bias as possible.

Choosing \(\lambda\)

In practice you need to specify the \(\lambda\) value to use in the ridge regression. Ideally you want to choose a value for \(\lambda\) that:

- Introduces the least amount of bias possible, while also

- Obtaining better sampling variances.

This is an impossible task without knowing the true values of the coefficients (i.e., the \(\beta\) values). There are, however, some empirical methods to help us in this endeavor. One of these methods is to create and evaluate a plot of the ridge trace.

Ridge Trace

A ridge trace computes the ridge regression coefficients for many different values of \(\lambda\). A plot of this trace, can be examined to select the \(\lambda\) value. To do this, we pick the smallest value for \(\lambda\) that produces stable regression coefficients. Here we examine the values of \(\lambda\) where \(\lambda = \{ 0,0.001,0.002,0.003,\ldots,100\}\).

To create this plot, we fit a ridge regression that includes a sequence of values in the lambda= argument of the lm.ridge() function. Then we use the tidy() function to summarize the output from this model. This output includes the coefficient estimates for each of the \(\lambda\) values in our sequence. We can then create a line plot of the coefficient values versus the \(\lambda\) values for each predictor.

# Fit ridge model across several lambda values

ridge_models = lm.ridge(achievement ~ -1 + faculty + peer + school, data = z_data,

lambda = seq(from = 0, to = 100, by = 0.01))

# Get tidy() output

ridge_trace = tidy(ridge_models)

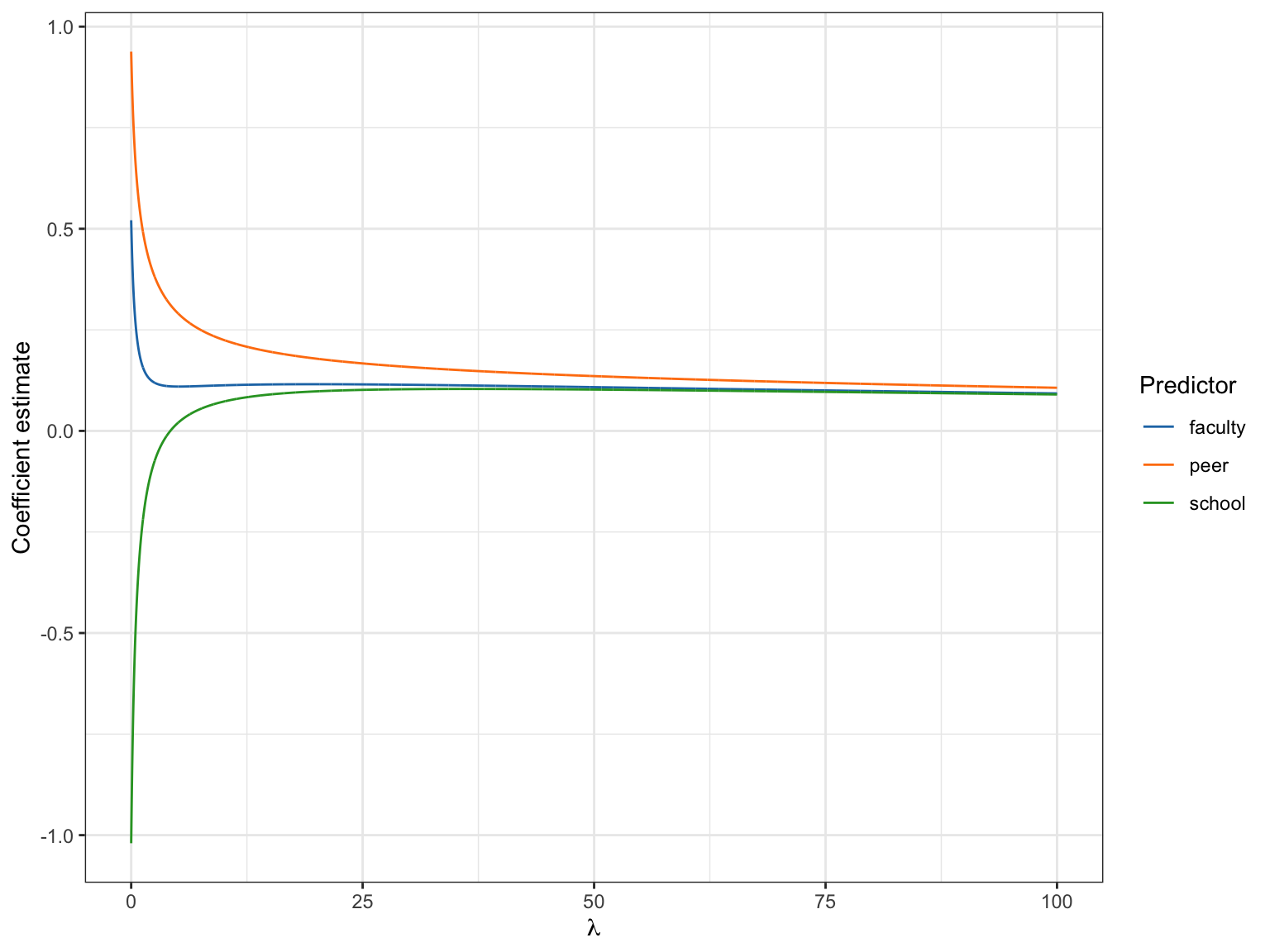

ridge_traceRidge plot showing the size of the standardized regression coefficients for \(\lambda\) values between 0 (OLS) and 100.

# Ridge trace

ggplot(data = ridge_trace, aes(x = lambda, y = estimate)) +

geom_line(aes(group = term, color = term)) +

theme_bw() +

xlab(expression(lambda)) +

ylab("Coefficient estimate") +

ggsci::scale_color_d3(name = "Predictor")

We want to find the \(\lambda\) value where the lines begin to flatten out; where the coefficients are no longer changing value. This is difficult to ascertain, but somewhere around \(\lambda=50\), there doesn’t seem to be a lot of change in the coefficients. This suggests that a \(\lambda\) value around 50 would produce stable coefficient estimates.

AIC Value

It turns out that not only is it difficult to make a subjective call about where the trace lines begin to flatten, but even when people do make this determination, they often select a \(\lambda\) value that is too high. A better method for obtaining \(\lambda\) is to compute a model-level metric that we can then evaluate across the models produced by the different values of \(\lambda\). One such metric is the Akiake Information Criteria (AIC). We can compute the AIC for a ridge regression as

\[ \mathrm{AIC} = n \times \ln\big(\mathbf{e}^{\intercal}\mathbf{e}\big) + 2(\mathit{df}) \]

where n is the sample size, \(\mathbf{e}\) is the vector of residuals from the ridge model, and df is the degrees of freedom associated with the ridge regression model, which we compute by finding the trace of the H matrix, namely,

\[ tr(\mathbf{H}_{\mathrm{Ridge}}) = tr(\mathbf{X}(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}) \]

For example, to compute the AIC value associated with the ridge regression estimated using a \(\lambda\) value of 0.1 we can use the following syntax.

# Compute coefficients for ridge model

b = solve(t(X) %*% X + 0.1*diag(3)) %*% t(X) %*% y

# Compute residual vector

e = y - (X %*% b)

# Compute H matrix

H = X %*% solve(t(X) %*% X + 0.1*diag(3)) %*% t(X)

# Compute df

df = sum(diag(H))

# Compute AIC

aic = 70 * log(t(e) %*% e) + 2 * df

aic [,1]

[1,] 285.8729We want to compute the AIC value for every single one of the models associated with the \(\lambda\) values from our sequence we used to produce the ridge trace plot. To do this, we will create a function that will compute the AIC from a given \(\lambda\) value.

# Function to compute AIC based on inputted lambda value

ridge_aic = function(lambda){

b = solve(t(X) %*% X + lambda*diag(3)) %*% t(X) %*% y

e = y - (X %*% b)

H = X %*% solve(t(X) %*% X + lambda*diag(3)) %*% t(X)

df = sum(diag(H))

n = length(y)

aic = n * log(t(e) %*% e) + 2 * df

return(aic)

}

# Try function

ridge_aic(lambda = 0.1) [,1]

[1,] 285.8729To be able to evaluate which \(\lambda\) value is assocuated with the lowest AIC, we need to compute the AIC for many different \(\lambda\) values. To do this, we will create a data frame that has a column that includes the \(\lambda\) values we want to evaluate. Then we use the rowwise() and mutate() functions to apply the ridge_aic() function to each of the lambda values. Finally, we can use filter() to find the \(\lambda\) value associated with the smallest AIC value.

# Create data frame with column of lambda values

# Create a new column by using the ridge_aic() function for each row

my_models = data.frame(

Lambda = seq(from = 0, to = 100, by = 0.01)

) %>%

rowwise() %>%

mutate(

AIC = ridge_aic(Lambda)

) %>%

ungroup() #Turn off the rowwise() operation

# Find lambda associated with smallest AIC

my_models %>%

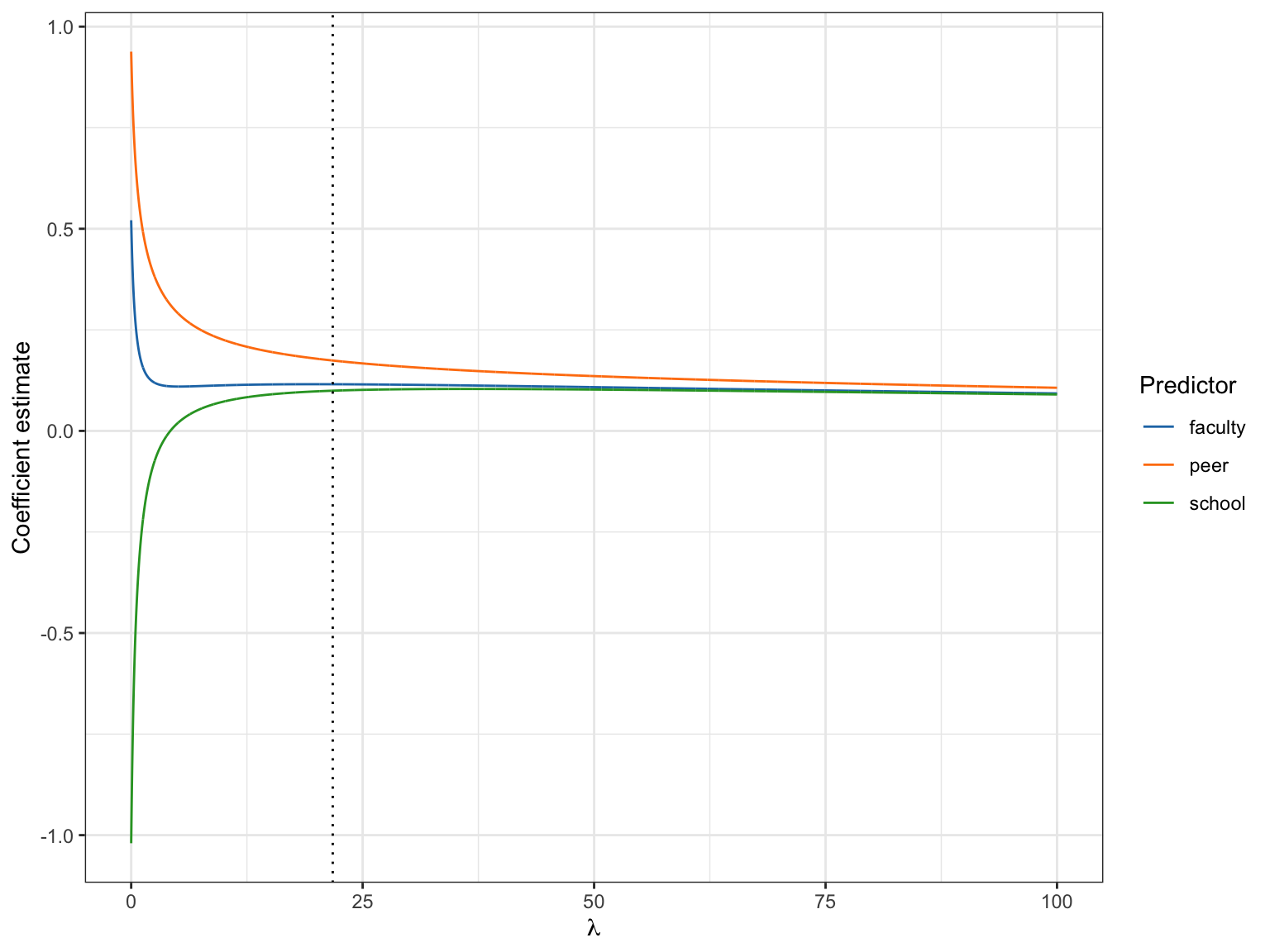

filter(AIC == min(AIC))A \(\lambda\) value of 21.77 produces the smallest AIC value, so this is the \(\lambda\) value we will adopt.

# Re-fit ridge regression using lambda = 21.77

ridge_smallest_aic = lm.ridge(achievement ~ -1 + faculty + peer + school,

data = z_data, lambda = 21.77)

# View coefficients

tidy(ridge_smallest_aic)Based on using \(\lambda=21.77\), the fitted ridge regression model is:

\[ \hat{\mathrm{Achievement}}^{\star}_i = 0.115(\mathrm{Faculty}^{\star}_i) + 0.174(\mathrm{Peer}^{\star}_i) + 0.099(\mathrm{School}^{\star}_i) \]

Estimating Bias

Recall that the ridge regression produces biased estimates which means that:

\[ \mathbb{E}(\hat{\beta})\neq\beta \]

The amount of bias in the coefficient estimates is defined as:

\[ \mathrm{Bias}(\mathbf{b}_{\mathrm{Ridge}}) = -\lambda(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}+\lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1}\boldsymbol\beta \]

where \(\boldsymbol\beta\) are the population coefficients from the standardized regression model.

Remember, for the OLS model that \(\lambda=0\). In that case,

\[ \begin{split} \mathrm{Bias}(\mathbf{b}_{\mathrm{OLS}}) &= 0(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}+0\mathbf{I})^{-1}\boldsymbol\beta \\[0.5em] &= 0 \end{split} \]

There is no bias in any of the OLS coefficients. Of course, as \(\lambda\) increases, the bias in the coefficient estimates will also increase. We can use our sample data to estimate the bias, it is likely a poor estimate, as to obtain the bias we really need to know the true \(\beta\)-parameters (which of course we do not know).

# OLS estimates

b_ols = solve(t(X) %*% X) %*% t(X) %*% y

# Compute lambda(I)

lambda_I = 21.77*diag(3)

# Estimate bias in ridge regression coefficients

-21.77 * solve(t(X) %*% X + lambda_I) %*% b_ols [,1]

faculty -0.4086492

peer -0.7703338

school 1.1277095It looks like the faculty and peer coefficients are biased downward and the school coefficient is biased upward in our ridge regression model. We could also see this in the ridge trace plot we created earlier.

# Ridge trace

ggplot(data = ridge_trace, aes(x = lambda, y = estimate)) +

geom_line(aes(group = term, color = term)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 21.77, linetype = "dotted") +

theme_bw() +

xlab(expression(lambda)) +

ylab("Coefficient estimate") +

ggsci::scale_color_d3(name = "Predictor")

In this plot, the estimates for the peer and faculty coefficients are being shrunken downward from the OLS estimates (at \(\lambda=0\)), and the school coefficient is being “shrunken” upward (closer to 0). This implies that the bias is simply the difference between the OLS estimates and the ridge coefficient estimates.

# Difference b/w OLS and ridge coefficients

tidy(ridge_smallest_aic)$estimate - b_ols [,1]

faculty -0.4094598

peer -0.7708210

school 1.1267430Sampling Variances, Standard Errors, and Confidence Intervals

Recall that the sampling variation for the coefficients is measured via the variance. Mathematically, the variance estimate of a coefficient is defined as the expectation of the squared difference between the parameter value and the estimate:

\[ \sigma^2_{b} = \mathbb{E}\bigg[(b - \beta)^2\bigg] \]

Using rules of expectations, we can re-write this as:

\[ \begin{split} \sigma^2_{b} &= \mathbb{E}\bigg[\bigg(b - \mathbb{E}\big[\beta\big]\bigg)^2\bigg] + \bigg(\mathbb{E}\big[b-\beta\big]\bigg)^2 \end{split} \]

The first term in this sum represents the variance in b and the second term is the squared amount of bias in b. As a sum,

\[ \sigma^2_{b} = \mathrm{Var}(b) + \mathrm{Bias}(b)^2 \]

In the OLS model, the bias of all the estimates is 0, and \(\sigma^2_{b} = \mathrm{Var}(b)\). In ridge regression, the bias term is not zero. The bias–variance tradeoff implies that by increasing bias, we will decrease the variance. So while the second term will get bigger, the first will get smaller. The hope is that overall we can reduce the amount of sampling variance in the coefficients. However, since the sampling variance includes the square of the bias, we have to be careful that we don’t increase bias too much, or it will be counterproductive.

The fact that the sampling variance for the coefficients is dependent on both the variance and the amount of bias is a major issue in estimating the sampling variation for a coefficient in ridge regression. This means we need to know how much bias there is to get a true accounting of the sampling variation. As Goeman et al. (2018) notes,

Unfortunately, in most applications of penalized regression it is impossible to obtain a sufficiently precise estimate of the bias…calculations can only give an assessment of the variance of the estimates. Reliable estimates of the bias are only available if reliable unbiased estimates are available, which is typically not the case in situations in which penalized estimates are used.

He goes on to make it clear why most programs do not report SEs for the coefficients:

Reporting a standard error of a penalized estimate therefore tells only part of the story. It can give a mistaken impression of great precision, completely ignoring the inaccuracy caused by the bias. It is certainly a mistake to make confidence statements that are only based on an assessment of the variance of the estimates.

Estimating Sampling Variance

In theory it is possible to obtain the sampling variances for the ridge regression coefficients using matrix algebra:

\[ \sigma^2_{\mathbf{b}} = \sigma^2_{e}(\mathbf{X}^\intercal \mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^\intercal \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}^\intercal \mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1} \]

where \(\sigma^2_e\) is the the error variance estimated from the standardized OLS model.

# Fit standardized model to obtain sigma^2_e

glance(lm(achievement ~ -1 + faculty + peer + school, data = z_data))# Compute sigma^2_epsilon

resid_var = 0.9041214 ^ 2

# Compute variance-covariance matrix of ridge estimates

W = solve(t(X) %*% X + 21.77*diag(3))

var_b = resid_var * W %*% t(X) %*% X %*% W

# Compute SEs

sqrt(diag(var_b)) faculty peer school

0.05482363 0.05670386 0.04133673 Comparing these SEs to the SEs from the OLS regression:

| Predictor | λ=0 | λ=21.77 |

|---|---|---|

| Faculty | 0.667 | 0.055 |

| Peer | 0.598 | 0.057 |

| School | 0.993 | 0.041 |

Based on this comparison, we can see that the standard errors from the ridge regression are quite a bit smaller than those from the OLS. We can then use the estimates and SEs to compute t- and p-values, and confidence intervals. Here we only do it for the school facilities predictor (since it is of primary interest based on the RQ) but one could do it for all the predictors.

# Compute t-value for school predictor

t = 0.09944444 / 0.04133673

t[1] 2.405716# Compute df residual

H = X %*% solve(t(X) %*% X + 21.77*diag(3)) %*% t(X)

df_model = sum(diag(H))

df_residual = 69 - df_model

# Compute p-value

p = pt(-abs(t), df = df_residual) * 2

p[1] 0.01886747# Compute CI

0.09944444 - qt(p = 0.975, df = df_residual) * 0.04133673 [1] 0.016957390.09944444 + qt(p = 0.975, df = df_residual) * 0.04133673[1] 0.1819315This suggests that after controlling for peer influence and faculty credential, there is evidence of an effect of school facilities on student achievement (\(p=.019\)). The uncertainty in the 95% CI suggests that the true partial effect of school facilities is between 0.017 and 0.182. The empirical evidence is pointing toward a slight positive effect of school facilities.

Bias–Variance Tradeoff: Revisited

Now that we have seen how the bias and the sampling variance are calculated, we can study these formulas to understand why there is a bias–variance tradeoff.

\[ \begin{split} \mathrm{Bias}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{Ridge}}) &= -\lambda(\mathbf{X}^{\intercal}\mathbf{X}+\lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1}\boldsymbol{\beta} \\[0.5em] \mathrm{Var}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{Ridge}}) &= \sigma^2_{\epsilon}(\mathbf{X}^\intercal \mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^\intercal \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}^\intercal \mathbf{X} + \lambda\mathbf{I})^{-1} \end{split} \]

Examining these two formulas, we can see that in the formula for bias, larger \(\lambda\) values are associated with increased bias. Whereas in the formula for sampling variance, increasing \(\lambda\) decreases the amount of sampling variation. This. in a nutshell, is the bias–variance tradeoff. Decreasing one of these properties tends to increase the other. The key is to find a value of \(\lambda\) that minimally increases bias to maximally decrease the sampling variances.

While ridge regression is one of the more popular shrinkage methods used in the social sciences, there are other shrinkage methods that have been developed for dealing with collinearity, including the LASSO [Tibshirani:1996] and elastic net (Zou & Hastie, 2005). These methods are similar to ridge regression in that they apply a penalty to the loss function (i.e., the SSE), albeit a different penalty than ridge regression.

However, both the LASSO and elastic net have been slow to be adopted by social scientists, despite both methods outperforming ridge regression in prediction accuracy and in producing simpler, more interpretable models (especially when the number of predictors is large). For more information about these methods, see James et al. (2013) and Goeman et al. (2018).

References

Footnotes

At least within the class of linear, unbiased estimators.↩︎